Tallinn’s civil defence also requires permanent funding, as a third of Estonia’s population relies on the ability of the country’s largest local municipality to provide assistance in the event of a major crisis or military attack. If the state is unable to respond on a large scale, Tallinn, according to a recent statement by the Government Office of the Republic of Estonia,1 should be able and willing to do so independently.

While building points of invincibilities to every city district is a good idea, Tallinn faces a significant challenge. To understand the impact of an attack on a city like Tallinn, consider the comparable populations of Mõkolajiv and Kherson, with populations of approximately 500 000 and 300,000, respectively.

The reality of Ukrainian cities includes not only the destruction of civilian infrastructure and housing, as well as the suffering of the people, but also the destruction of local government buildings. Cities have been targeted precisely for their population density and the vulnerability of people living in apartment buildings.

Shopping malls and transport hubs have been and will continue to be hit, as well as administrative buildings with rescue stations – we can build points of invincibilities and turn district administration buildings into public hiding places, but they are of little use in the aftermath of the bombings.

Of course, the points of invincibilities have their place, but there is no getting away from the need for a strategic plan. Its creation and implementation, however, necessitate the mobilisation of sufficient human and financial resources, but most importantly, political will and the courage to make a decision. A strategic plan, civil defence strategy, or, in the case of Tallinn, civil defence development plan, should at least include the following elements:

- the Tallinn Municipal Police Department is reorganised into the Tallinn Civil Defence Department;

- Tallinn’s budget establishes the principle that 2% of the city’s budget will be dedicated to municipal civil defence;

- there must be a separate unit in the city’s Strategy Centre with a strategic overview of the state of civil defence in the city system, from education to medical facilities across the city;

- given their size, city districts should also have civil defence experts to assist the city’s leadership in both planning and crisis management.

A comprehensive solution is required

The concept of a comprehensive system and its necessity have been debated in Tallinn for years, but it has yet to be articulated, at least in terms of civil defence. This is understandable, as there is no comparable ability or desire at the national level, where there is no overarching plan or goal to strive for. There is only a desire to hang around, to put posters on public facilities declaring them bomb shelters, and to maintain a semblance of stability, which is occasionally revived by a few local authorities arguing with the central government.

The reality of civil defence at the local level reflects what is happening in the nation.

The establishment of the Strategy Centre has been one of the best steps forward in the capital’s development, and it is now time for the civil defence perspective to be integrated into it. This vision is needed in a variety of fields, including urban planning and education. For example, it could have prevented a situation in which the new state gymnasiums, both newly built and planned for Tallinn, did not include a requirement for bomb shelters during the spatial planning stage.

Similarly, when the centre of Tallinn was excavated, underground bomb shelters could have been planned and built, possibly linked together to form a system, as is common in many European cities. However, this is only possible if there is a systematic view of the budget; planning such investments requires time, strategic documents, and political will.

Among other things, under the leadership of the Strategy Centre, there must be a shift towards planning public space for dual-use while also providing civil defence capabilities throughout the city, as space is one of the most pressing issues. This thinking must also extend to the job description of the city architect if such a position is to be reinstated. If transportation tunnels are to be built in Tallinn, they must be designed so that they can be converted into bomb shelters with blast doors, as in Prague.

Furthermore, if the city constructs new recreational and sporting facilities, it would be prudent to do so underground, either entirely or in multiple stories. Many fitness centres in Helsinki have been built underground, and there is no reason why Tallinn cannot follow suit. Parts of the public transport system should also be relocated underground; this is necessary for improved mobility, cleaner air, and a sense of public safety, but it is also part of a tangible comprehensive system.

The era we live in requires both vision and the courage to make decisions. Tallinn has all of the prerequisites to take the necessary steps now and become a national leader in civil defence. If the city takes action on civil defence issues, it sends a signal to the residents that they, too, should take action, and that real action by the city will result in action by residents. Hopefully, it will also force the central government to finally decide whether the general population, as in Europe, is worthy of civil defence.

A strategic perspective will also assist the municipality in better justifying to the central government exactly what additional funding is required for. The question of funding is obviously important, but it must be preceded by an understanding of what the money is being requested for.

Regardless of the composition of the city administration or the fact that there is a significant gap in the legislation, now is the time for a substantive debate on the next steps for the city’s civil defence. If the capital does not act, how can smaller municipalities with even fewer resources in all respects build a system?

How should municipalities like Vormsi or Rõuge address this when the capital already struggles to protect its residents in the public space? It is no longer enough to admit that we communicate frequently with our Ukrainian colleagues, exchange ideas, and everything continues to improve. This is insufficient, lame, and inappropriate for Estonia’s largest municipality, which has a budget of more than one billion euros this year.

Above all, real steps need to be taken,3 as the lack of strong civil defence is the weak link in the country’s defence capacity. Otherwise, we will be trapped in the “strong in theory” trap, where everyone understands that the situation is really bad, understands that something must be done, but what is not it is not.

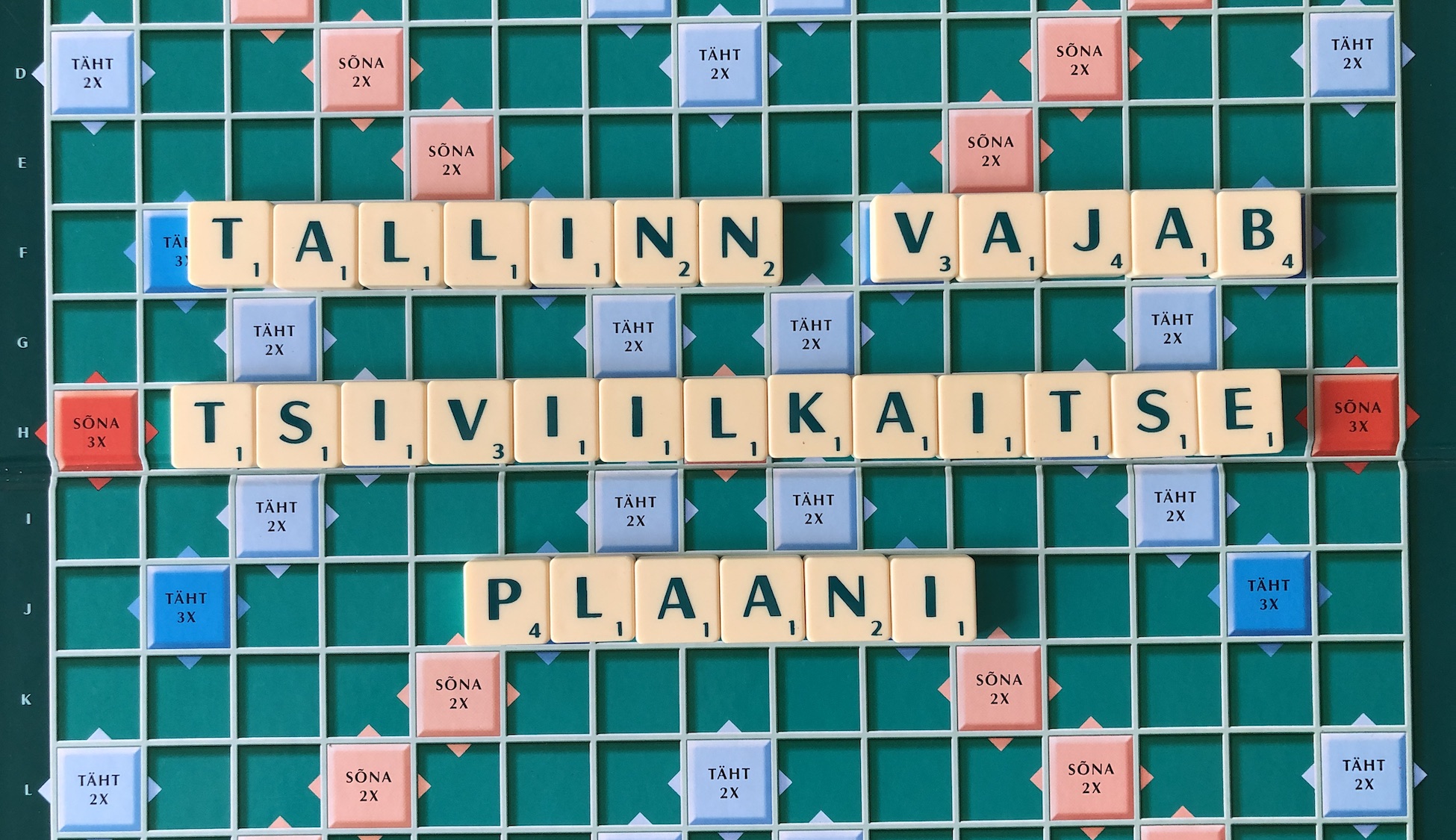

× The op-ed (Hannes Nagel) was previously published on April 15, 2024 on the Postimees web portal. Photo: Tallinn needs a civil defence plan (Crisis Research Centre, 2024).